This chapter was originally published as Black, S., & Allen, J. D. (2018). Insights from educational psychology part 8: Academic help seeking. The Reference Librarian, 60(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1533910. Minor revisions have been made from the version published in Reference Librarian.

Academic reference librarians are in the business of helping students and faculty find information. To succeed in our work, those who could use our help must avail themselves of the opportunity. Unfortunately, librarians are keenly aware that although we are willing and able to assist people, many will not ask for our help. In this chapter we explore the various reasons why patrons may be reluctant to ask for help, and in our Takeaways for Librarians section conclude with suggestions for actions to help overcome that reluctance.

Seeking Help as an Adaptive Learning Strategy

The many adjustments students must make when they attend college include learning how to do more complex research in a library that is usually much larger than what they are used to. The higher expectations for research and the vastness of resources available can cause confusion, frustration, and anxiety (Mellon, 1986). Kuhlthau’s (1991) model of the information search process included a stage of exploration typified by confusion and doubt. The fundamental purpose of librarians being available for reference is to help students navigate their way through the sticking points in the search process. Yet many students do not ask for the help we offer.

Before we describe the various reasons why students who could use help fail to ask for it, it is worth reviewing the clear benefits of seeking academic help. Nelson-Le Gall (1985) argued against the prevailing view at the time that asking for help is a degrading activity to be avoided. She reconceptualized help-seeking as an adaptive learning strategy to be encouraged as a way for students to master material, rather than as a sign of dependence to be discouraged (Nelson-Le Gall, 1985). Help-seeking is an adaptive learning strategy. At the heart of her argument was a distinction between help that is instrumental to learning how to succeed on one’s own versus help that is intended to execute a solution to the immediate problem. Instrumental help-seeking need not be stigmitizing or self-threatening if it effectively helps one cope with current difficulties (Nelson-Le Gall, 1985). The idea is now broadly accepted that knowing when and how to ask for the right kind of help for the right reasons is an adaptive learning strategy that should be supported and encouraged. Ideally all help will be instrumental, but realistically sometimes executive help is all students are ready and willing to accept at their time of need (Collins & Sims, 2006). When librarians understand the barriers to asking for help described in this chapter, we may be more effective at persuading seekers of executive help to appreciate and accept instrumental help.

Karabenick and Dembo (2011) described eight steps in the help seeking process:

- determine whether there is a problem

- determine whether help is needed or wanted

- decide whether to seek help

- decide on what type of help to get (instrumental or executive)

- decide on whom to ask

- solicit help

- obtain help

- process the help received.

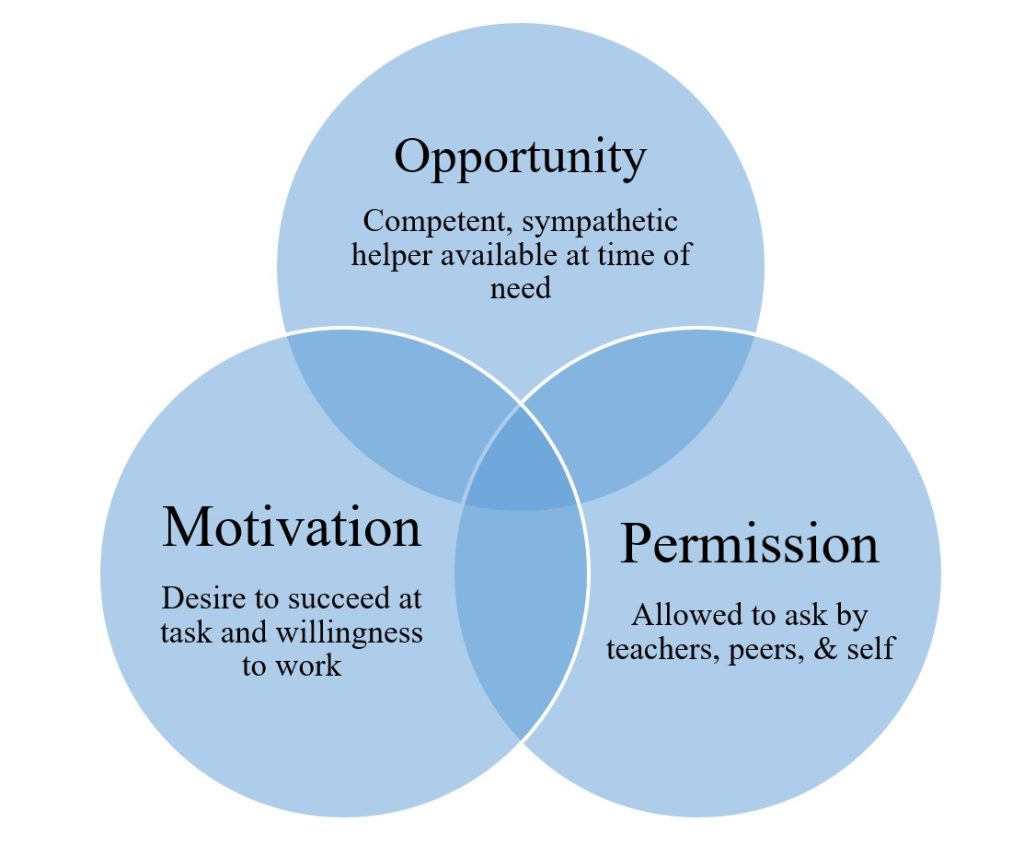

Effective implementation of these steps requires cognitive, social, and emotional competencies that can be taught to students who may lack the needed skills (Karabenick & Dembo, 2011). Effective instrumental help requires three prerequisites depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Prerequisites for Asking for Academic Help

A student in need of help must have an opportunity to ask for and receive help, the motivation to ask, and the permission to solicit help. The opportunity to ask for help requires a competent and sympathetic help giver available at the time of need. In practice this means not only that the service is available, but also that the student takes advantage of the service in a timely manner. The student needs to be motivated to succeed at the task and be willing to put forth sufficient effort. Finally, the student must perceive that they have permission to ask for help (or have the self-confidence to ask without permission).

Chapter 2 emphasized the key role of self-regulation in academic achievement. Self-regulation of learning involves forethought, performance, and self-reflection (Zimmerman & Campillo, 2003). Asking questions and seeking help are important elements in the performance phase of self-regulated learning. What makes asking for help different from most elements of self-regulation is the social nature of openly admitting that help is needed.

We organize the reasons why students who could use academic help may not ask for it in four broad categories: 1) goals and motivations, 2) social interaction, 3) personal characteristics, and 4) learning environment. A summary from the educational psychology literature of reasons for avoiding help are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Why students won’t ask for help

| GOALS AND MOTIVATIONS |

| Fatalist attitude |

| Lack of motivation to complete task |

| Unwilling or unable to devote time and effort |

| Concern for social status |

| SOCIAL INTERACTIONS |

| Peer influence and group dynamics |

| Inability to articulate why they are asking for help |

| Preservation of self-image and self-esteem |

| Perceive potential help provider as not the relevant person to ask |

| Desire to avoid being a burden |

| PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS |

| Desire for autonomy and self-reliance |

| Fear help provider will lack empathy or ability to understand the situation |

| Discomfort with disclosing information about oneself |

| Overconfidence |

| LEARNING ENVIRONMENT |

| Lack of opportunity to ask for help |

| Lack of awareness of available help |

| Fear of negative consequences of revealing need for help |

| Past negative experiences |

Impact of Goals and Motivations on Help Seeking

Our understanding of the psychological context of asking for help is informed by four prominent theories regarding goals and motivations: 1) achievement goal orientation, 2) mindset, 3) attribution of causes, and 4) social goal orientation. Researchers have identified two broad types of achievement goal orientation: mastery and performance. A student with a mastery goal orientation desires to succeed at a task because they value the benefits of achievement. Since seeking help supports learning, self-improvement, and mastery, a mastery goal orientation supports appropriate help seeking behaviors (Ryan, Pintrich, & Midgley, 2001). In contrast, a student with a performance goal orientation focuses on doing better than others, receiving recognition, or attaining praise for ability. Since asking for help may signal that one is not more competent than others, a performance goal orientation tends to increase avoidance of help seeking (Ryan et al., 2001).

Dweck (1986) has done extensive work in collaboration with fellow psychologists to understand the role of mindset on motivation and goal setting. She found that students’ theories of intelligence impact their goals, confidence, and behaviors. Some individuals have an entity theory of intelligence, i.e. believe that we each have a fixed amount of intelligence. Others have an incremental theory, i.e. believe that intelligence is malleable (Dweck, 1986). She has found that having a mindset that intelligence is malleable supports mastery goal orientation and leads to positive outcomes in education and in life (Dweck, 2006). A mindset that intelligence is malleable supports mastery goal orientation and leads to positive outcomes in education and in life.

A mindset that intelligence is fixed tends to lead to fatalist attitudes toward tasks. A student who concludes “I’m just not good at this” is unlikely to ask for help because they don’t see the point in putting forth effort for a preordained result. The fixed intelligence mindset can also lead to making excuses for failure due to bad luck or circumstances out of one’s control, rather than to the effort expended.

Attribution theory addresses whether and why students make excuses or accept responsibility. Attributions for outcomes of prior performance directly impact a student’s decision to seek help (Ames & Lau, 1982). Say a student did poorly on their last assignment that required using library resources. They might attribute their poor performance to one or more of several factors, e.g. personal ability, effort expended, difficulty of the task, level of interest in the topic, quality of the assignment, or bad luck. Students who accept responsibility and attribute outcomes to their own efforts are significantly more likely to take advantage of help than are students who make excuses (Ames & Lau, 1982).

Some of the more obvious reasons why students do not ask librarians (or anyone else) for help happen to be the most challenging to counteract. A student may simply lack motivation to complete an assignment because they have no personal interest in it and they do not value whatever external rewards are offered. Students may also be unwilling or unable to devote the necessary time and effort to succeed. That could be because other activities crowd out time available, they do not set the assignment as a priority, or they simply procrastinate. When students do not set a goal to successfully complete an assignment and are unmotivated to work on it, there is precious little a librarian can do to help. Karabenick and Knapp (1988) found that students expecting a grade of D or lower almost never took advantage of academic help.

Ryan and Pintrich’s (1998) analysis of students’ help seeking behaviors included the influence of social intimacy goals versus social status goals. An individual with an intimacy orientation desires to form and maintain positive relationships with peers. An individual with a social status goal orientation is more interested in being visible and gaining prestige. Students with a social intimacy goal orientation are more likely to seek help because they appreciate the opportunity to interact and are less concerned with potential loss of social status. However, a recent experiment to measure college students’ attitudes about asking for help revealed very low agreement with the statement “I would not want my friends to know if I ask a librarian for help” (Black & Krawczyk, 2017, p. 280). But this finding that students had little concern about peer’s opinions may have been due to self-reporting of behavior that may not be reflected in real life.

Impact of Social Interactions on Help Seeking

Social goal orientations are but one aspect of how peer influences and group dynamics impact individuals’ willingness to ask for help. In Chapter 5 on learning as a social act, we presented an example to illustrate Bandura’s (1989) model of the interactions of personal characteristics, the learning environment, and behavior. In that example, a student observes a peer successfully ask for a librarian’s help and the modeled behavior is enough for that student to overcome their reluctance to ask for help. The converse can also occur. If peers express the opinion that asking a librarian is uncool or a sign of incompetence, the likelihood of asking for help will likely decrease. Also, if no one else is asking for help, it takes additional courage to be the first to approach the potential help giver.

A crucial social influence on asking for help lies in an individual’s ability to articulate the reason for asking for help. When a person decides to ask for help and has chosen who to ask, the next step is to formulate the question. In what was for many years the standard text on reference librarianship, the late Bill Katz described the challenge of question formation this way: “Failure of the person putting the inquiry to make it clear to the librarian is the greatest road block to reference communication” (Katz, 2002). We know that few opening questions in the reference interview are well formulated. What we do not know is how often patrons never ask because they have trouble articulating their information need. Patrons may not ask because they have trouble articulating their information need. People need an account that satisfactorily justifies asking for help (Grayson, Miller, & Clarke, 1998), a narrative to answer for themselves, “What am I asking and why am I asking it?” Librarians can help overcome this barrier primarily by sending the message that we understand this difficulty, that it is normal and natural, and that it is okay to ask a poorly formulated question.

Asking for help may create threats to self-image and self-esteem, especially for individuals with performance and social status goal orientations. Karabenick (2004) found that agreeing with the statement “I would feel like a failure if I needed help in this class” was strongly correlated (r = .64, p < .001) with unwillingness to seek help, as was the desire to not appear stupid. McAfee (2018) asserted that shame lies at the heart of library anxiety, which in turn results in students not asking librarians for help. She described shame as “imagining or perceiving a negative evaluation of oneself through the eyes of others, as well as through one’s own eyes, e.g. feeling incompetent, ridiculous, stupid, alienated, or unimportant” (McAfee, 2018, p. 246).

Members of underrepresented groups may be particularly prone to threats to self-image or self-esteem, and concern over being stereotyped can adversely affect willingness to get help. Stereotype threat impacts individuals when they become concerned about conforming to a negative stereotype, for example that women are not good at engineering (Steele, 1997). Collins and Sims (2006) note that “the threat of being perceived as less capable than others could cause some students to disengage from the very resources that should be helpful to them” (p. 212). For instance, stereotype threat might cause a female student in an engineering course to not ask for help out of fear of confirming the negative stereotype that women do not make good engineers. One study of Latino adolescents found that while individuals with high self-esteem were likely to get help when appropriate, low-achieving males and immigrants with little English proficiency tended to withdraw from sources of support (Stanton-Salazar, Chávez, & Tai, 2001). Another interpersonal reason to not ask for help is a desire to avoid being a burden to the help giver. Vinyard, Mullally, & Colvin (2017) were disconcerted that some students imagined a quota on how often they could ask questions of their librarians, quoting a student “I don’t want to be a burden, I’m only going to use [the librarian] when I really, really need her” (p. 262).

Impact of Personal Characteristics on Help Seeking

The student’s quote above demonstrates the role of personal autonomy and self-perception of competence in help seeking behavior. Many students have a commitment to self-reliance and strong desire to achieve independently. “The perception of help seeking as a dependent behavior competes with the desire for autonomy and impedes students’ asking for help when they need it” (Ryan et al., 2001, p. 106). Perceptions of competence also impact students’ willingness to seek help. A student confident in their competence to complete a task is less likely to perceive asking for help as a threat to self-esteem. One who doubts their competence might avoid asking for help out of fear that it will make them look stupid (Ryan et al., 2001).

We wish to emphasize that while students bring personal characteristics such as desire for autonomy and self-perceptions of competence to the moment of asking a question of a librarian, those characteristics were largely created by social interactions. A main point of Vygotsky’s highly influential socio-cultural view of learning is that we become who we are through interactions with others (Wertsch & Tulviste, 1992). We use the term personal characteristics here to denote thoughts and emotions based on prior experiences that individuals bring to the current context.

One barrier to asking for help that can arise from prior experience is fear that the potential help provider will lack empathy or be unable to understand the need. As should be obvious from the reasons students don’t ask for help listed in Table 1, asking for help can be emotionally stressful. Being shown lack of empathy or understanding will compound that stress and make help seeking a profoundly negative experience. Asking for help can be emotionally stressful. Students need a sense that the help giver has been in a similar situation at some time themselves and that they have a good understanding of the context (Grayson et al., 1998). Even for an individual with strong social confidence, perceived lack of empathy or understanding can lead a student to conclude that asking will end up wasting rather than saving time.

Another barrier is innate reluctance to reach out. This could be due to shyness or an inherent tendency to keep things bottled up (Grayson et al., 1998). Asking for help is a form of self-disclosure, and some individuals are uncomfortable with disclosing their thoughts and feelings to others.

Among the personal characteristics that impact help seeking behavior, we have found one of the most common to be overconfidence. The main finding from Black & Krawczyk’s (2017) intervention to shift students’ attitudes regarding library research was that reading a narrative of students’ experiences that included asking for help significantly decreased agreement with the statement “I feel confident today about my ability to do library research.” Many students simply do not know what they do not know. Within psychology a version of this phenomenon is known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Individuals with low levels of knowledge tend to have a cognitive bias toward believing they know more than they actually do (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Students may fail to ask for help simply because they have not reached a level of knowledge that enables them to be aware of what they have left to learn.

Impact of Learning Environment on Help Seeking

Adaptive help seeking can only occur in learning environments that offer opportunities to get effective instrumental help. A lack of competent, sympathetic helper is one of the most obvious barriers to asking for help. Here we refer to what is offered in the system, rather than a student’s failure to take advantage of available resources. Appropriate design of academic library reference services should make this barrier uncommon. Students who procrastinate may wish for help at 1 a.m., but we presume that we can expect self-regulated learners to ask for help during working hours.

A frequently encountered barrier to asking for help is ignorance of what the help giver can provide. It is distressingly common for students to not understand how reference librarians can help, so students ask elsewhere or not at all (Head & Eisenberg, 2009). A recent qualitative study of how college students responded to being stuck in their research processes also found that few students were aware of librarians’ role and purpose (Thomas, Tewell, & Willson, 2017). Beisler & Medaille (2016) did an innovative study of college students’ help seeking behaviors using drawings of research processes and concluded “In addition to alerting students to their availability, librarians need to make students explicitly aware of the different types of help that they can provide, since it seems clear from this study that students do not connect their different research needs with possible library assistance” (p. 399).

Another potential barrier is not a lack of knowledge about help givers, but rather past negative experiences with reference librarians or other academic support providers. One or more previous negative experiences can discourage students from asking for help, even when the help givers are different individuals. Past experiences can also impact potential fear of negative consequences for revealing a need for help. In many cases the help is needed at least in part because the student has not put forth expected effort in a timely manner (Pillai, 2010). A student may anticipate that they will face punishment for being in the position of having to ask for help.

What is to be done?

Reference and instruction librarians have long had a good intuitive sense of the aforementioned reasons why students may be reluctant to ask for help, even if they may not have been familiar with the educational psychology research on help-seeking behaviors. A recent literature review on reasons why students avoid seeking help from librarians cites a rich trove of publications spanning over a century (Black, 2016). Analyses of reasons and remedies for not taking advantage of reference services include Swope and Katzer’s (1972) “Why Don’t They Ask Questions?” and Bunge’s (1984) historical review of the literature on interpersonal factors in the reference interview. The literature makes clear that well-designed reference services and thorough training of reference librarians can lower the barriers to asking for help.

The Reference and User Services Association section of the American Library Association developed Guidelines for Behavioral Performance of Reference and Information Service Providers (RUSA, 2008). The desired behaviors are well attuned to minimizing the negative impacts of students’ feelings about asking for help. Yet the RUSA Guidelines presume that people will overcome reluctance and have the gumption to ask. Librarians can only implement the Guidelines when we have patrons to interact with.

We make some specific recommendations in the Takeaways for Librarians section below. Broadly speaking, the main takeaway from research on academic help seeking behavior is the critical role of sympathy and patience. It is very important to remember that one interaction can have significant long-term effects. Providing friendly and useful executive help today may lead to a more fruitful provision of instrumental help later on. But if the student has a negative experience and never returns, the opportunity to be truly helpful is lost. Interactions with students give us chances to demonstrate our helpfulness and convey that it is normal to feel uneasy about asking for help.

Takeaways for Librarians

- Acknowledge and be sympathetic that asking for help is emotionally stressful in various ways.

- How students feel during and after an interaction with a librarian can have influential and long-lasting effects.

- Provide executive help when necessary, but always promote and work toward instrumental help to build competence and autonomy.

- Promote the mindset that intelligence is malleable and that ability comes with effort.

- Tell students that it is normal to struggle with formulating a question and justifying why one is asking for help, and that it is okay to ask a librarian for help before having a well-crafted question.

- Just because a student desires to be autonomous does not mean they don’t need help.

- Convey to students that confusion and frustration are a normal part of the research process and can be overcome with effort.

- Challenge students with tasks that make them aware of what they do not know yet.

- Use instruction sessions as an opportunity to raise awareness of librarians’ role and express understanding and sympathy for the stresses of the research process.

- Continue to raise awareness of how librarians can be helpful through marketing and promotion of reference and instruction services.

- Consistently follow the RUSA Guidelines for Behavioral Performance of Reference and Information Service Providers

Recommended Readings

Ames, R., & Lau, S. (1982). An attributional analysis of student help-seeking in academic settings. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(3), 414–423. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.74.3.414

Russell Ames collaborated with Sing Lau to expand upon Sing’s dissertation on the reasons why students choose whether to seek help when appropriate. They found a student’s decision is based on three factors: prior performance, attribution of reasons for prior performance, and information about the usefulness of help. Students who attribute performance to luck (versus ability or effort) or who make excuses for the outcome tend to avoid asking for help. Students who believe they are capable of succeeding but recognize they have not yet put forth sufficient effort will ask for help, but only if the source of help is perceived as potentially useful.

Beisler, M., & Medaille, A. (2016). How do students get help with research assignments? Using drawings to understand students’ help seeking behavior. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 390–400. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.010

Molly Beisler and Ann Medaille studied students’ research behaviors by having them draw their processes and explain what was depicted the drawings. This creative and insightful qualitative method revealed the role of help seeking in context of the full research process. Very few of the students sought help from librarians. The most popular source of help was friends and family. Feelings of stress or panic only led to seeking help about a third of the time, in part because students who procrastinate deprive themselves of meaningful opportunities to get help. The authors found that the students who did solicit help exhibited more sophisticated research habits than those who did not seek help, and concluded that help seeking is itself an effective research strategy.

Collins, W., & Sims, B. C. (2006). Help Seeking in Higher Education Academic Support Services. In S. A. Karabenick & R. S. Newman, (Eds.), Help seeking in academic settings: Goals, groups, and contexts. (pp. 203–223). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Although Collins and Sims address writing centers, first-year experience programs, academic advising and other support services, the reasons for students not seeking help and what can be done to motivate students to get help are directly relevant to academic librarianship. The three overarching goals of academic support resource programs are to increase awareness, motivate students to use services, and promote self-regulated learning. Support programs are geared toward helping students seek mastery of material, use good time management, and become successful independent learners. Yet many students are looking for a quick fix. A successful support program works to give realistic help at point of need with a long-range goal of developing self-regulated learners.

Karabenick, S. A., & Dembo, M. H. (2011). Understanding and facilitating self-regulated help seeking. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 126, 33–43. doi:10.1002/tl.442

Stuart A. Karabenick has authored and co-authored dozens of studies on academic help seeking. This paper includes a useful summary of findings on how to match effective types of help with students’ individual needs. Help-seeking is a multi-stage process: identify problem, decide if help is needed to solve problem, choose helper, ask for help, get the help, and process the help received. Interventions to assist each stage of the process address students’ abilities to plan, self-monitor progress, and self-evaluate results. Support should include helping students deal with their learning-related emotions and attitudes, particularly recognizing and overcoming irrational beliefs. Explicit coaching and practice on how to formulate and ask questions can be beneficial.

Karabenick, S. A., & Knapp, J. R. (1988). Help seeking and the need for academic assistance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 406–408. doi:/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.406

A study of 612 undergraduates compared students’ help seeking with expected grades and perceived need for academic help. Students who expected a grade between C and B+ were most likely to seek help. Students who expected a grade of D or below did not ask for help. This study provided quantitative data to support the widespread impression that those who need help most are least likely to seek it. Failing students tend to attribute their situation to lack of ability or bad luck and thus tend to feel helpless and experience negative emotions such as sadness, guilt, embarrassment, hopelessness, and resignation. Poor performers face the double burden of cognitive and emotional obstacles to obtaining needed help.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371.

Although not about help seeking per se, Carol Kuhlthau’s classic description of students’ research processes is fundamental to understanding the context of students’ use of library reference services. Kuhlthau identified six stages in the research process: initiation, selection, exploration, formulation, collection, and presentation. Students tend to start with uncertainty, experience initial optimism, then work through confusion, frustration and doubt to gain clarity and a sense of direction. The phase of confusion and doubt is usually accompanied by some anxiety. Reference interviews should adapt to meet the preliminary, exploratory, comprehensive or summary information needs at each stage in the research process.

Nelson-Le Gall, S. (1985). Help-seeking behavior in learning. Review of Research in Education, 12, 55–90. doi:10.2307/1167146

Sharon Nelson-Le Gall’s seminal article challenged the prevailing point of view that asking for help indicated lack of academic ability and was thus to be discouraged. She reconceptualized help-seeking as an adaptive learning strategy rather than as a sign of dependence. She made an important distinction between executive help seeking (having someone else solve the problem by executing a solution) and instrumental help seeking (learning how to solve the problem). Multiple benefits accrue to students who receive instrumental help.

Pillai, M. (2010). Locating learning development in a university library: Promoting effective academic help seeking. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 16(2), 121–144. doi:10.1080/13614531003791717

Mary Pillai gave practical how-to advice for facilitating help seeking in a Learning Commons context. Her writing is especially readable, the literature review is thorough, and the recommendations are based real life experience at De Montfort University in Leicester, United Kingdom. Students’ main sources of help in descending frequency of use were: course tutors, fellow students, working harder, friends and family, the web, handouts, and librarians. Keys to effective support services are encouraging students to be pro-active, being accessible, and modeling self-reflective engagement.

Ryan, A. M., Pintrich, P. R., & Midgley, C. (2001). Avoiding seeking help in the classroom: Who and why? Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 93–114. doi:10.1023/A:1009013420053

The authors focus on why adolescents who realize they could use academic help avoid seeking it out. Key factors are performance level, self-esteem, and perceptions of competence. Students with a performance goal orientation (striving to outperform others or achieve an extrinsic reward) tend to perceive seeking help as an indicator of being less competent than others. Students with a social goal orientation tend to see seeking help as a threat to their status among peers. Ideally, students will have a mastery academic goal orientation and an intimacy social goal orientation, as those orientations support willingness to seek academic help.

Works Cited

Ames, R., & Lau, S. (1982). An attributional analysis of student help-seeking in academic settings. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(3), 414–423. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.74.3.414

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Beisler, M., & Medaille, A. (2016). How do students get help with research assignments? Using drawings to understand students’ help seeking behavior. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 390–400. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.010

Black, S. (2016). Psychosocial reasons why patrons avoid seeking help from librarians: A literature review. Reference Librarian, 57(1), 35–56. doi:10.1080/02763877.2015.1096227

Black, S., & Krawczyk, R. (2017). Brief intervention to change students’ attitudes regarding library research. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 56(4), 277–284. doi: 10.5860/rusq.56.4.277

Bunge, C. A. (1984). Interpersonal dimensions of the reference interview: A historical review of the literature. Drexel Library Quarterly, 20(2), 4–23.

Collins, W., & Sims, B. C. (2006). Help seeking in higher education academic support services. In S. A. Karabenick & R. S. Newman (Eds.), Help seeking in academic setting: Goals, groups, and contexts. (pp. 203–223). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY, US: Random House.

Grayson, A., Miller, H., & Clarke, D. D. (1998). Identifying barriers to help-seeking: A qualitative analysis of students’ preparedness to seek help from tutors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 26(2), 237–253.

Head, A. J., & Eisenberg, M. B. (2009). Lessons learned: How college students seek information in the digital age. Project Information Literacy. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED535167

Karabenick, S. A. (2004). Perceived achievement goal structure and college student help seeking. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(3), 569–581. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.96.3.569

Karabenick, S. A., & Dembo, M. H. (2011). Understanding and facilitating self-regulated help seeking. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 126, 33–43. doi:10.1002/tl.442

Karabenick, S. A., & Knapp, J. R. (1988). Help seeking and the need for academic assistance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 406–408. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.406

Katz, W. A. (2002). Introduction to reference work (8th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361–371.

McAfee, E. L. (2018). Shame: The emotional basis of library anxiety. College & Research Libraries, 79(2), 237–256. doi:10.5860/crl.79.2.237

Mellon, C. A. (1986). Library anxiety: A grounded theory and its development. College & Research Libraries, 47(2), 160–165.

Nelson-Le Gall, S. (1985). Help-seeking behavior in learning. Review of Research in Education, 12, 55–90. doi:10.2307/1167146

Pillai, M. (2010). Locating learning development in a university library: Promoting effective academic help seeking. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 16(2), 121–144. doi:10.1080/13614531003791717

RUSA. (2008). Guidelines for behavioral performance of reference and information service providers. Retrieved June 14, 2018, from http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidelinesbehavioral

Ryan, A. M., & Pintrich, P. R. (1998). Achievement and social motivational influences on help seeking in the classroom. In S. A. Karabenick (Ed.), Strategic help seeking: Implications for learning and teaching. (pp. 117–139). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Ryan, A. M., Pintrich, P. R., & Midgley, C. (2001). Avoiding seeking help in the classroom: Who and why? Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 93–114. doi: 10.1023/A:1009013420053

Stanton-Salazar, R. D., Chávez, L. F., & Tai, R. H. (2001). The help-seeking orientations of Latino and non-Latino urban high school students: A critical-sociological investigation. Social Psychology of Education, 5(1), 49–82. doi:10.1023/A:1012708332665

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613

Swope, M. J., & Katzer, J. (1972). The silent majority: Why don’t they ask questions? RQ, 12(2), 161–166.

Thomas, S., Tewell, E., & Willson, G. (2017). Where students start and what they do when they get stuck: A qualitative inquiry into academic information-seeking and help-seeking practices. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(3), 224–231. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2017.02.016

Vinyard, M., Mullally, C., & Colvin, J. B. (2017). Why do students seek help in an age of DIY? Using a qualitative approach to look beyond statistics. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 56(4), 257–267. doi:10.5860/rusq.56.4.257

Wertsch, J. V., & Tulviste, P. (1992). L. S. Vygotsky and contemporary developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 28(4), 548–557. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.4.548

Zimmerman, B. J., & Campillo, M. (2003). Motivating self-regulated problem solvers. In J. E. Davidson & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of problem solving. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771.009